This week, both The New York Times and the Michelin Guide revealed their lists of the best “new” restaurants in New York City. At The Times, this meant compiling a list of fourteen restaurants that three critics—one former and the two interim replacements—either already reviewed or enjoyed privately at some point this year. For Michelin’s anonymous inspectors, this involved awarding restaurants coveted stars or a “Bib Gourmand” as part of an annual ceremony. For New York chefs and restaurateurs, these are the most coveted honors alongside the James Beard Awards, whose nominees are announced in early April.

Of the twelve new restaurants to earn stars, five are either omakase or a similar intimate tasting experience (Nōksu is a 15-seat counter serving tiny bits of Korean-inspired seafood on large plates). This is boring, but makes sense given NYC’s eagerness for clubstaurants, favoring experience and “vibes” over food. Omakase and a restaurant like The Corner Store are on opposite ends of the dining horseshoe, offering either asceticism or lavish indulgence to the point of exclusivity. People do not talk about these places because they went, they go there because they want to talk about them. But at least The Corner Store, with its everything bagel croutons and lobster frites, is very New York; who goes to the city for sushi?

It’s also no surprise that industry executives see stars less as important drivers of business than as as a “feather in the cap” for chefs. Earning a star is something to put on a resume with the promise of success further down the road. If you don’t initially work at a place (or multiple) of renown, like Carmy in The Bear, being able to say you were part of a team that earned a restaurant its star(s) still bolsters the chances of earning your own one day. There are also the James Beard Awards, which are even more about industry than its food. Imagine the Golden Globes but every category was somehow for directors, and then the voting body also gave an award to the critic who probably used to be a director. Just like the HFPA does not matter to moviegoers, the James Beard Awards do not matter to diners. They would rather watch TikToks telling them which restaurants to go to, or peruse a list of places that allow them special reservation privileges via their AMEX.

But Michelin still persists, and it acknowledges the uncomfortable tension of restaurant-going in a large city that other institutions do not. Good food often comes at a price, and sometimes that price is affordable, depending on your taste. If restaurants were merely expensive, and not codified because of their expense, no one would go. But when you are given a Michelin star, cost is baked into the award; a three-star rating implies the food is worth a “special journey.” The Michelin guide started as an implicit way to get French people spending more money on their cars, after all. And now its inspectors have figured out a way to convince people to spend the most on not much, at all. Yes, tasting menus have many courses, but we have all seen the portion sizes. When I see painstakingly plated food replete with microgreens, all I can think of are TikToks where insane people with eating disorders try to convince you that a small amount of broccoli sprouts contains the same “nutrients” as a recommended daily serving of vegetables. Food is better, and even better for you, when it has tiny stems! And it looks sexy on a social media feed, too.

Though stars are coveted by chefs, and diners with large credit limits surely pay attention to them, it is unclear who Bib Gourmands are for besides the anonymous inspectors that award them. Rick Camac, restaurateur and executive director at the Institute of Culinary Education, said his two Bib Gourmand recognitions were “virtually worthless” to both his businesses and diners. He continued: “The average diner probably doesn’t think very much about it.” This is true. When you take a look at the full list awarded Bib Gourmand distinction in New York City this year, the picture becomes clearer; there are two restaurants—Cervo’s and Tolo—in Dimes Square with a Bib Gourmand. Of course, if I were a Michelin Inspector with a hankering for blowing off steam where there’s a vermouth pairing for everything and even the dessert is boozey, I’d award Cervo’s a Bib Gourmand, too. Other awardees run the gamut from “fusion that a French person would think is cool” (Cantonese-American, Vietnamese-Mexican) to “oh, I’m in town to review Per Se again, let's catch up over dinner in Brooklyn because you have a kid and live there now” (“LORE,” Untable). A Bib Gourmand is basically a high-profile foodie’s Spotify Wrapped, but you can’t even send their story to a friend to make fun of it.

The New York Times list leans more democratic, with multiple named critics selecting restaurants of all cuisines from all boroughs at all price-points. This amounts to a funny microcosm of “how things are,” where being able to eat tacos while sitting on top of an upside down paint bucket is lauded alongside a new shawarma shop owned by an Israeli chef. Nice job, Pete Wells. Still, the list has more personality than Michelin, and includes actual blurbs about the restaurants. Whether or not the writing is good—salsa is described as “kicky,” and “touches” are described as “cheffy”—it intrigues enough to motivate diners. Unlike a Bib Gourmand, Rick Camac notes that positive word in The Times can drive steady and noticeable traffic to a restaurant, which is good for both chefs and diners; if a restaurant is excellent, but receives no attention, not that many people get to experience it, and it closes forever: this happens often, only about 50% of restaurants survive past five years.

But this closure rate is basically the same for any type of small business in the United States. Restaurants, though, are afforded special attention, because eating is something we all do, and the plight of the chef is somehow more glamorous and relatable than the plight of a guy who just can’t seem to keep his roofing business afloat. During the pandemic, there was a strong outpouring of support, both emotionally and monetarily, for restaurants. Though some say that this has waned—New York City is now fining even the most beloved restaurants skirting outdoor dining rules—I think it is stronger than ever. Now, everything is awesome, and The New York Times (along with Eater and Grub Street) keep it that way.

In recent years, influencers have made a habit of building content around “reviewing” restaurants already heaped with praise. Of course, you can read a review of PopUp Bagels on The Infatuation, but wouldn’t it instead be more awesome and “digestible” if a former star of The Bachelor posted a video of himself eating there? Some of these influencers pay for their meals, but some demand free meals in exchange for posting, which is a complicated relationship to navigate. What if a restaurant doesn’t receive enough attention from the post? What if they receive too much attention? Why are influencers going to certain restaurants in the first place? Most don’t consider themselves “food critics,” so it's not to decide if somewhere is good or bad; instead, it’s to grow their personal brand and eat a free meal, feigning concern about “being mean,” in the process. Most of these influencers never say anything negative: every restaurant is awesome.

One influencer is particularly locked into all these threads, making it her mission to try every restaurant on The NYTimes 100 Best list. Kaitlyn Lavery has almost 300k followers on TikTok, where she posts videos of herself reviewing food that The Times has already deemed the “best” of NYC. Still, Lavery gives her “honest thoughts,” even if it amounts to saying something would “literally never be her top pick.” Her videos are rapid and frenetic, and not always about restaurants on an existing list (though, now that there’s a list for everything, there’s plenty of crossover). In a landscape of NYC food critique where two of the most prominent critics suddenly leave their posts, and another stalwart is laid off, why isn’t legacy media hiring someone like Lavery?

In his final column as The NYTimes food critic, Pete Wells writes about how dining out has become increasingly alienating: we book tables via screens, order via screens, and pay via screens not just at McDonald’s, but now even at lauded restaurants like Mattos Hospitality’s Lodi. He also details watching the landscape shift from restaurants cultivating regular customers and long-term patrons to instead reaching for viral food creations and influencer clientele. Wells recognizes that none of these Michelin-starred restaurants actually care about customers, and none of these influencers actually care about food.

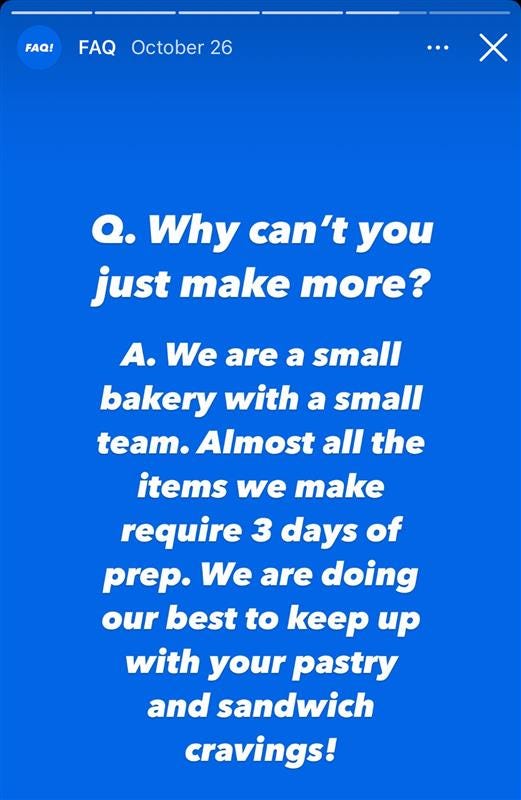

But, Wells and his ilk have in recent years been a part of the problem. Peter Luger is an institution; it does not need to be panned, people will still go there. Wells’s interim replacement panning Carbone makes no sense either, and is as self-serving as a restaurant striving for stars. The last truly negative review I read was of a Tom Colicchio restaurant, but even that was tepid (and, the restaurant, Vallata, is actually quite good). A culture of niceness has permeated criticism of all kinds, as Clare pointed out here: yes, unlike the reviews of large studio blockbusters, critics are still handing out negative reviews, but only to those who can afford it. Why shouldn’t you also pan a bakery that enforces exclusivity, selling out pastries each day many hours before the posted closing time? Sure, the food might be okay, but is the experience?

Five years ago I would have read these lists of star-earners and worthwhile meals as soon as they went live, making note of where I wanted to visit. Now, I simply do not care. I’ve become zen in my pursuit of food: I notice things that are new when walking by them on the street, and I try them without asking someone first. The other week, for example, I saw a new bakery opening inside a former Dunkin location. I stopped in on their soft opening day and purchased a malted cinnamon roll, which was delicious. Yesterday, my girlfriend asked me if I had heard of this very same place. “Influencers have been going there,” she said. I’m sure they have.

I go to the city for sushi all the time ...

radio acts like every day is a new sneaker launch. you make croissants!!!