Last month, Vulture published a piece of writing about “Obamacore.” Nate Jones wonders: Is Kamala Harris bringing it back? The cultural output of Obama’s two terms were, of course, optimism, celebrity, self-consciousness, cringe. Jones references Glee, Hamilton, and Taylor Swift’s 1989 to explain how art veered from “snark” of the Bush years towards the redemption of a new, more liberal generation. When Obama was President, comedians became public philosophers, sitcoms became introspective, humanistic teaching tools, and The Food Network gave way to Bon Appetit’s YouTube Channel.

Despite the election of Donald Trump in 2016, Obamacore had a long tail. Girls ended in 2017, Broad City in 2019, and The Good Place in 2020. The most popular Bon Appetit videos that started the trend of foodfluencer-cum-chefs were uploaded during the meatiest parts of Trump’s presidency. Watching relatable Millennials like Claire Saffitz and Brad Leone make (pre-COVID) sourdough or “gourmet Skittles” epitomizes the sense of “adult kindergarten” in that era of Internet content. Who has forty minutes to watch someone make gourmet Starburst? 10mm people heckin’ do!

While celebrity chefs like Paula Deen and Mario Batali had fallen from grace, Bon Appetit’s star only rose. Food culture was now also work culture, the Bon Appetit test kitchen virtually interchangeable with any open-floor-plan-office where you might open Photoshop to design graphics in Millennial Pink. “Coworkers” stream in and out of frame, other “chefs” or “journalists” like Molly Baz and Alex Delany popping in to steal a bite of whatever that day’s main talent is preparing. In one video, Saffitz says to Chris Morocco: “You guys are tasting Petrossian caviar, and I’m gonna eat some instant ramen.” One of the top comments on this video reads: “Claire is the kind of person you wanted to be paired with in class for a group project.” Is this supposed to feel like school?

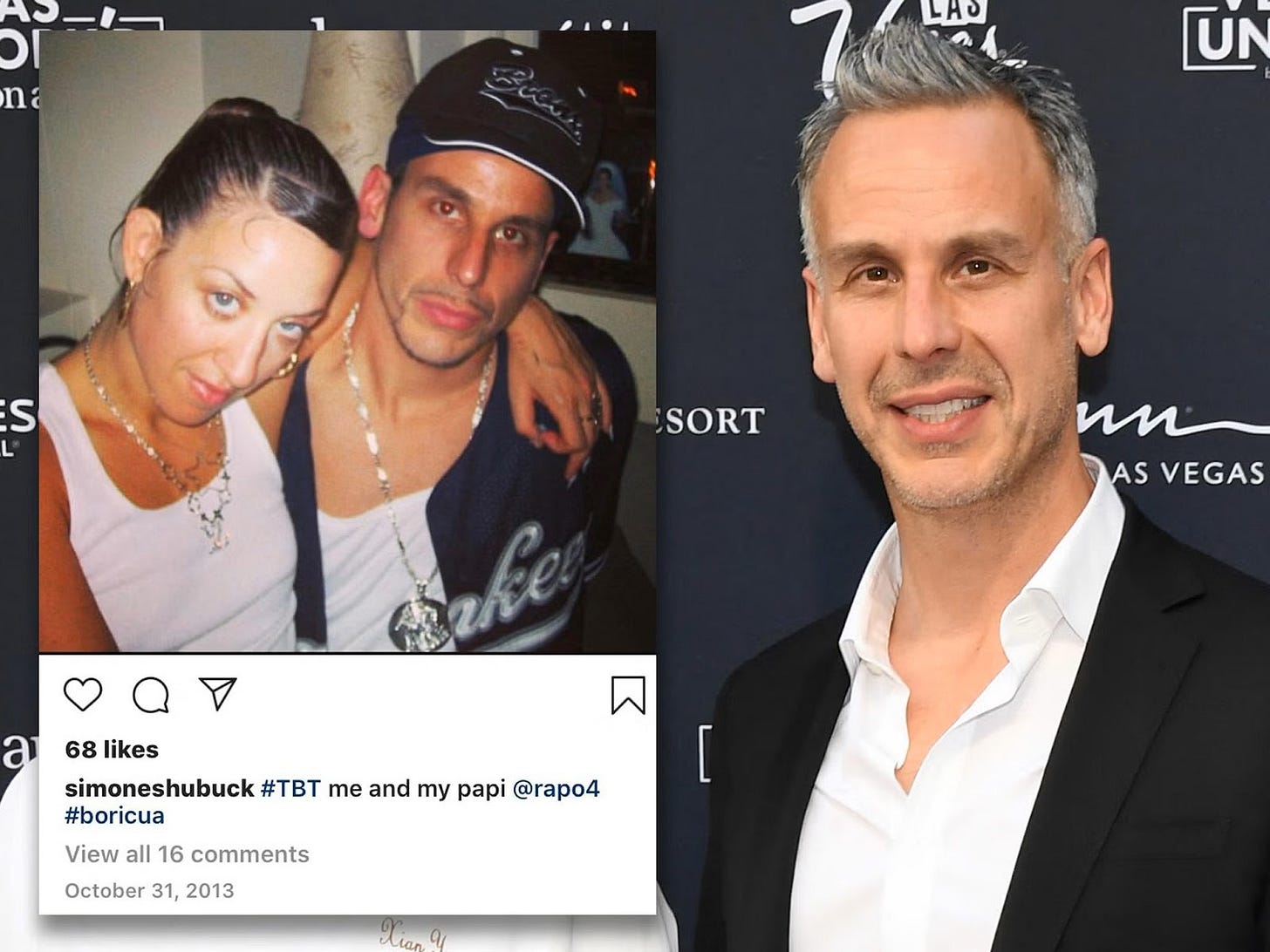

But the cultural backlash that engulfed most Obamacore relics eventually came for Bon Appetit, too, when an old photo resurfaced of the magazine’s editor-in-chief in brownface. Shortly thereafter, assistant food editor Sohla El-Waylly began detailing on her Instagram story how the company had used her presence in videos as a mere “display of diversity.” This was in 2020, the last year of Trump’s presidency. Something new was beginning.

These “chefs” have remained active, no longer under the Bon Appetit banner but taking long-form content to their own YouTube channels, and new, short-form videos elsewhere. During COVID, TikTok exploded in popularity, surpassing 1 billion active users and spawning copycat formats from Meta and Google in the form of Reels and Shorts. Since 2020, food content has been shaped by this new medium. Like Obamacore, this content is relatable, but now in a more immediate way, no longer displayed in widescreen.

While Jones’s Vulture article offers a definition of Trump-era culture as a rebuke to the Obama years, it fails to define Trumpian Culture on its own terms. We all know when Obamacore began to end: one day Louis C.K. was guest starring on Parks and Recreation, the next he was not. But when did Trumpian Culture fully take over? The lines are muddled, COVID blurring boundaries between years and presidencies and cultural touchstones. Within the last four years, most food-based content has become wordless ASMR-fueled montages pretending to tantalize the palate, but really meant to tickle the brain. It plays at a breakneck pace, not meant to teach but to be marveled at. This is foodfluencing in the Trumpian age: make it look “the best,”even if incredibly haphazard, and keep it moving so nobody can ask any questions. Scrolling the feed of any contemporary foodfluencer is like watching Donald Trump give a speech. Sure it can be funny, but it moves too quickly and often nonsensically. Even the people creating this food content take on a Trumpian air. If Obamacore was celebrity-obsessed, Trumpcore is self-obsessed.

Consider Owen Han, the former USC lacrosse player and self-ascribed “Sandwich King.” Han has amassed over 100mm likes and 4.3mm followers on TikTok, with another 2.2mm followers on Instagram. He has a new cookbook out this October from HarperCollins titled Stacked: The Art of the Perfect Sandwich. He even received a pull-quote from celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay: “Owen is a food star for a new generation…I can’t wait to try more of his creations from this book!” But what are these “creations?”

Han specializes in a messy, Trumpian style of recipe-making and food styling. Meat is slapped into a pan, vegetables haphazardly chopped, and oil and vinegar glugged with reckless abandon. Stirring is exaggerated, lids are slammed, meat is shredded up close for maximum ASMR-ability. There are usually no words in these videos, and no recipes in the captions, either. But Han always shows himself taking a bite, which is always slathered in a cheese or cheese-like substance, and never un-blowtorched. It is novel—spectacular—to watch someone appoint themselves the king of something and explode in popularity simply by appealing to the most basic human impulses. While Trump did this with his speech rhetoric, it’s easily transferable to beauty, fashion, and especially food. As Ryan Detert—the CEO of influencer marketing agency Influential—notes: “We are hungry every few hours, it’s literally an insatiable vertical.”

Han has collaborated with many others in this burgeoning milieu, like Joshua Weissman and Henry Laporte, a.k.a. Salt Hank (who also has a book out this October, too, called Salt Hank: A Five Napkin Situation). While creating similar content to Han’s, both Weissman and Laporte also veer into vulgar, macho, and vaguely homophobic territory that seems styled after some amalgamation of Alton Brown and Matt Rife. It is Brad Leone, but Gen Z. For instance, on his website, Laporte sells a seasoning called “Holy Shit That’s Zesty.” Unlike Guy Fieri or even Action Bronson, who these Trumpian foodfluencers are clear descendents of, there is nothing down to earth about them, yet their popularity only increases.

But when these guys share their spotlight with a female star of legacy food media, they freeze. There is no substitute for actual charisma, not a messy sandwich, nor being “hot.” While making a video with Padma Lakshmi, Han seems nervous and out of his element, nearly crying from the spice of too many chilis. While Lakshmi riffs that the chutney they’ve created is only “junior-high-level heat,” Han tries to impress her, asking “how do we get to varsity?” Everything from that point is uncertain (“... so four more?”). There’s no confident slapping or chopping, and despite the camera’s innate love for Lakshmi, the video drags. Trumpian content is not sustainable, not applicable across generations.

A video with Martha Stewart is even worse. When Han suggests they toast slices of bread with butter in a pan, Stewart replies: “Oh I would never do that, I have a Salamander.” Han has no idea she is talking about a broiler, responding, “like a pet?” Later in the video, when Han asks Stewart if she likes his homemade buttermilk ranch dressing, she replies that it’s “good enough,” to which he nervously looks off camera and says “alright, I’ll take it.” This is Trumpian content under active fissure; when too many words interrupt the messy mise-en-place-SMR, the videos become as cringeworthy as Obamacore seems now. But Trumpian food content extends beyond cooking.

Jack’s Dining Room is a restaurant reviewer whose goal is “finding the best food and experiences in the world.” He wears an oversized trucker hat with the words “YES CHEF.” printed in bold across the front panel, and approaches all his videos as though he’s describing the craziest night out he’s ever had. His videos are often prefaced with thumbnails that speculate: is this the best _____ in America? In the entire world?

While reviewing Datz Deli, a Guyanese and Caribbean hole-in-the-wall on the Lower East Side, Jack begins his video by filming the owners, calling them “honestly, some of the nicest people I’ve ever met.” He then waxes platitudes about the American dream in AAVE before calling the DatMacPatty—a beef patty stuffed with mac and cheese and oxtail sandwiched between slices of Guyanese butter bread—an “insane experience.” He struggles to parse what he even likes about it, basically recounting the ingredients of the sandwich before wondering how someone came up with “this creation.” The food is front and center, but unlike the classic Obamacore program Diners, Drive–Ins, and Dives, the owners of the place never get interviewed. All we get is Jack and his nothing-burger of words.

Not all Trumpian foodfluencers are new, though, with even Bon Appetit alumni adopting this new mode of production. Molly Baz is the worst offender, combining sloppy cooking with bracingly outdated aesthetic ambitions. This has made her a “2X New York Times bestseller,” owner of a beautiful Los Angeles home, founder of a wine company, and author of phrases like “cae sal” and “big titty cookies.”

While at Bon Appetit, Baz’s content masqueraded as “cute,” but she was always bound to break loose and reign supreme under the Trumpian food content regime. She astonishes in her drunken propensity to cause and evade controversy in equal measure. Will her son grow up to be a Barron, or a Baz Jr.?

Because TikTok necessitated Trumpian foodfluencing, and our attention spans are ever-shortening, this mode of content production and consumption should persist despite Trump’s failure to win in 2020, and, probably, 2024. But, while Nate Jones posits that Kamala Harris’s soaring popularity could signal a return to Obamacore optimism, I believe the days of 40mm views on a 30 minute YouTube video are gone.

Instead we are slowly, senilely falling headfirst into Bidencore food content, characterized by time chasms and simulated sleep paralysis. When you watch a video from A.J. Befumo, Big Justice, and The Rizzler, your eyes glaze over not because your brain is being stimulated, but because it is not. When Big Justice takes a bite of a sandwich and stares wide-eyed and blankly at the camera, or when A.J. repeats the same phrase over and over again in the same cadence, time moves differently. A two-minute video can easily feel like 20. These characters bring “the boom,” effortlessly memeing themselves without much to promote apart from a generic brand of positivity. Their recurrent, infantile catchphrases and mannerisms are reminiscent of Biden’s first three years in office, and A.J.'s long-running gambit to thrust himself and his family into the limelight is reminiscent of Biden’s entire political career. They are lodestars for an entirely new brand of influence, but the uncertainty around this year’s election threatens their existence as a mere blip in influencer history.

If Kamala Harris wins the presidential election, short-long content like that of the Befumo family is here to stay. Her reputation among Twitter users as a wine mom and benzo addict would inspire content less frenetic and Trumpian, more sleepy—like Biden. Perhaps Molly Baz is the perfect person to bridge those gaps between the former, current, and future styles of content creation, blending Trump’s vulgarity, Harris’s drunken frivolity, and Biden’s dead eyes into one sickening cocktail. Any way you slice it—sloppily, or in an overproduced test kitchen—what comes next will likely be devoid of “Hope.”

didn't know how badly i needed to read a piece like this to feel less crazy

this piece gets 5 booms